JEFFREY ST CLAIR

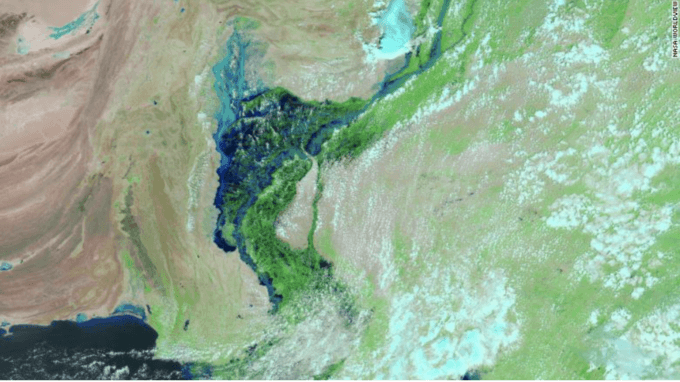

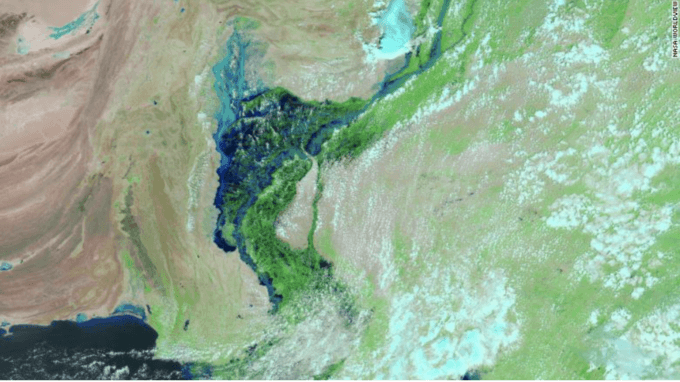

The scale of the destruction defies the

imagination. There are images and maps. But still you can’t quite wrap

your mind around it. With reason. We’ve never seen anything like this.

Never experienced it. Heard stories about it. There’s nothing to compare

it to, not even the Biblical floods. We’ve gone beyond our own myths

and legends.

A third of an entire country–a big country,

a country the size of Turkey and Venezuela–lies underwater, inundated

by fierce floods from all directions.

Thousands of miles of roads have been wiped

out. Hundreds of bridges washed away. Rail lines and airports

submerged. Nothing getting in, nothing getting out. The entire nation

brought to a standstill. A nation with nuclear weapons and an unstable

government, bordered by a hostile regime which has demonstrated every

inclination to take devious advantage of Pakistan’s devastated

condition.

Fields flooded, crops lost, livestock drowned.

Dams crumbled, power stations shorted out, transmission lines toppled, water treatment plants swamped.

Refineries, factories, hospitals and schools engulfed.

At least 220,000 houses were destroyed

(imagine all of the houses in Spokane demolished), maybe a million more

suffering some kind of damage, many beyond repair. At least 33 million

people–more than the population of Texas and Oklahoma combined–at least

temporarily displaced by the storms that have ravaged Pakistan since

late June.

At least 1,200 have died, 400 of them

children. More are missing. More than 330,000 people (about the size of

Cincinnati) are living in camps with no idea when they can return home,

how they will get there or what they will return to.

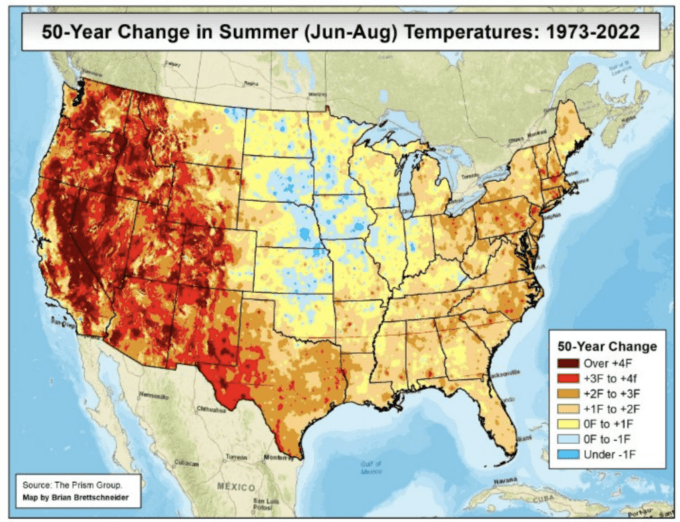

One of the fastest warming bodies of water

on the planet, the India Ocean is becoming a simmering cauldron, cooking

up heat waves and super-monsoons. This year the heat–heat almost beyond

the point of human survivability–came first, in two back-to-back waves

in May and June. Then came the rains. Rains like few other regions on

earth have ever experienced. Rains that swelled the ancient Indus River

over its banks and beyond its floodplains, creating a giant lake 100

kilometers wide almost overnight, which remains visible from space. A

lake which can’t be drained, because there’s no place to pump the water

to.

The rains that drenched Sindh were 784%

above the average for August. The rains that flooded Balochistan were

500% above normal. As much as 40 inches more than normal. Numbers so

high they don’t really have a meaning.

One searches for a precedent and finds

nothing even remotely close. This is now the precedent. This is the new

benchmark. We’re told we must adapt. Adapt to what? Cataclysm? How?

But the floods of August weren’t just

driven by extreme rains, they were also charged with runoff of from

collapsing glaciers in the Karakoram, Himalaya, Hindu Kush and Pamir

Mountains, producing torrents of water crashing down from 20,000-foot

peaks. Pakistan has more than 7,000 alpine glaciers, more than any place

outside of the polar regions. And this glaciers have been melting

10-times faster than their historic average over the last two centuries.

Pakistan, a country responsible for less than 1% of global carbon emissions, now faces the 8th highest climate risk in the world. But it’s coming for all of us, eventually, regardless of the level of culpability. There’s no place to hide.

Ecological time is moving very fast now, so

fast that we risk losing our bearings as a species, losing our

connections to the landscape of the past, the very terrain that defined

our existence, our ways of living, our sense of who and where we are.

What were once fields are now lakes, what were once glaciers now

cascades.

And yet the floods of Pakistan are a mere

prelude, an overture for the future that awaits us. There’s no going

back now, no bridge fuel to the past, no carbon capture time machine, or

nuclear techno-fix wormhole out of our predicament. At this terminal

point, such fantasies are only a measure of our failure to confront how

we got to where we are.

COUNTERPUNCH

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2022/j/O/EpAR82Soy87oQ5r7ek9g/100764433-brasilia-df-07102022-jair-bolsonaro-df-o-presidente-jair-bolsonaro-pl-com-o-apresentador.jpg)